We went back to Trinity again, this time for the full treatment: full tour, guided by a tame student, and then the Kells manuscript. Walking along it en route, I was struck again by how much Grafton Street reminds me of Madison's State Street—buskers, entertainers, and street artists all happily co-exist with the foot traffic rushing past. Today, several artists in sand were busily sculpting sleeping dogs. Why dogs? No idea.

Our guide for Trinity's official tour was a student who introduced himself as Stephen. Tall and slender, he had a mop of wavy strawberry-blond hair, indigo-blue eyes, and chiseled features—in all, a thoroughly dangerous young man. There was a glint of humor in his eye, though. When he mentioned that the campus had no school of veterinary medicine, I enquired with great solicitousness what they did when a student took ill.

He turned a wintry eye on me for a bare moment, and replied that student health wasn't an issue for the university administration, since they could easily summon a pediatrician. Thereafter, he enlivened the canned script with anecdotes and acerbic observations, to the great pleasure of his audience.

The tour lasted a scant half an hour, and covered the same buildings and sculptures we saw on our first visit. At the end, we stopped to chat with Stephen, who had, he said, just finished his bachelor's degree, and was to start work on his doctorate in September. His specialty was to be bandits, and he was especially interested in the likes of Jesse James and Ned Kelly—interesting subject matter, I have to agree.

|

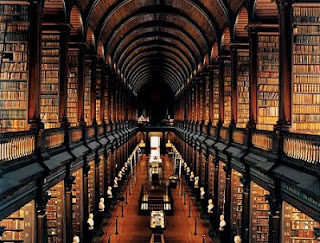

| Trinity Library |

The chief benefit of the tour was now ours: unlimited time in the Trinity library, with access to the Book of Kells exhibit. The preface to the Book is very thorough, with the Book of Dimma (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Book_of_Dimma) open on display, with all kinds of information on how medieval books were made, pigments used, parchment-making, book-binding techniques, and a dozen other things.

The Kells manuscript (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Book_of_Kells) itself is housed in a separate room, with the Book of Durrow (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Book_of_Durrow) and the Book of Armagh (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Book_of_armagh) in the same case. The room is dim, to protect the fragile manuscripts, which lie in a large case, glass-topped, with brushed-aluminum sides for leaning on to look closely at the manuscripts. Only one small quibble: the reflective glass case makes it difficult to see the books at times; Trinity, please copy....!

I've waited 35 years to see the Kells manuscript, which was open to the beginning of the Gospel of St. Matthew. Tour groups would come in, and I would politely step aside while they took a fast "But it's nothing exciting!" look. When they left, I re-applied myself to the case, studying the fineness of the calligraphy, and the intricacy of the knot work in the carpet page. Tom cheerfully tolerated this for more than an hour, until even he grew restive enough to start getting grumpy.

He dislodged me, and we moved on to the library's Long Room. Though it now houses more than 200,000 of the university's oldest books, they had only the smallest fraction of the current number when it was built. The scale is truly glorious, but the room itself is neither self-important nor forbidding: It's paneled in wood, now dark with age, that invites visitors to dip into the shelves and get comfortable.

Display cases down the center of the room held more of the library's delights. Among the most stunning were the incunabulae—books from the dawn of printing. There was a page from Gutenberg's Bible—not his first run, his very. First. Book. There was one of Caxton's, and one of Wynkyn de Word's as well; being in the same room as all three of those would be about the same deal as being in the same room with Shakespeare, Chaucer, and Donne. Mind-bending.

There was also a little French Book of Hours, late 14th century high Gothic, glowing like a jewel in the display case, and one of John Speed's maps of Leinster dating from the 16th century.

Off to one side, in a case by itself, was a harp—a clairseach (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Clairseach) The oldest harp in Ireland, some 600 years of age, it was made of willow, with brass strings. The only other thing I could have wished for was a recording of its voice, since it had been refurbished. If you're not familiar with the Irish harp, this is a very good introduction....

Lovely, isn't it?

No comments:

Post a Comment